Aymar Embury II — Unsung Hero of the New York City New Deal

Frank da CruzSee photo gallery of Embury New Deal projects See table of Embury New Deal projects

Bronx NY, November 2019

Last updated: 31 March 2022

When you think of architects who left their mark on New York City, who comes to mind? McKim, Mead, and White? I.M. Pei? Anybody else? Probably not!

Meet Aymar Embury II, member of President Roosevelt's Advisory Committee on Architecture 1934-43[2] and New York City Parks Department's chief architect from 1934 until the end of the Great Depression, and well beyond. In this capacity, he is said to have designed or supervised the design of over six hundred public projects in New York City[2]. He was a well-heeled, prosperous, and highly-regarded upper-crust architect who for some 20 years had specialized in elegant homes for the wealthy. He certainly did not take the Parks job for the money. More likely he took it on because at a time when unemployment in New York City exceeded 30%, he would be designing projects that would employ tens of thousands of jobless workers and once built, many of these projects would improve the lives of struggling families. Anyway, he liked his new Parks Department job better than his other ones because "it's such a madhouse"[3].In some ways Embury's public-spirited New Deal work diminished his own architectural legacy. Quite aside from the fact that he was now designing structures for ordinary people rather than estates in the Hamptons, there was the WPA's quite proper insistence on the least expensive construction materials — cheap concrete and bricks — to be able to hire the most workers. This was fine with Embury; in fact, he became a veritable master of the Aesthetics of Concrete[4]. The downside was that such gems as his Orchard Beach pavilion would decay and turn ugly over time. Yet it is a tribute to the value and impact of his New Deal creations that at least twenty of them have achieved landmark status and now, after decades of shameful neglect, many of them are being restored to their original glory.

I have no special knowledge of Embury and I know of no biography of him although he certainly deserves one. (What would Robert Moses have been without him?) He must have worked long hard days years on end to bring so many public works to fruition, with little recompense and not much recognition either since most NYC New Deal structures are not credited by the Parks Department to any particular architect, nor indeed to the very New Deal funding and labor that made them possible. No matter, Embury's work speaks for itself; it ranges from the humble and workaday (comfort stations, drinking fountains, ticket booths) to the monumental and magnificent:

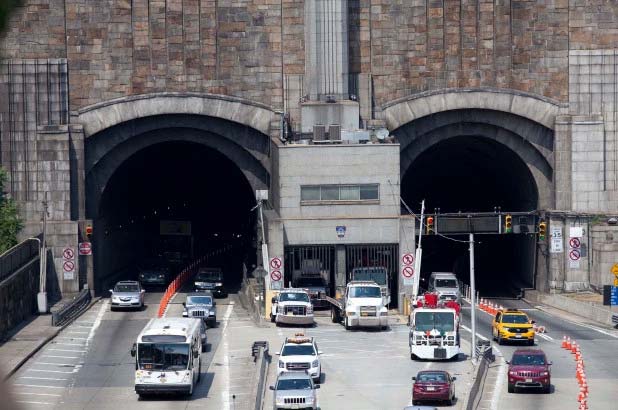

- The Lincoln Tunnel

- The Triborough Bridge

- The Marine Parkway Bridge

- The Bronx-Whitestone Bridge

- The Henry Hudson Parkway and Bridge

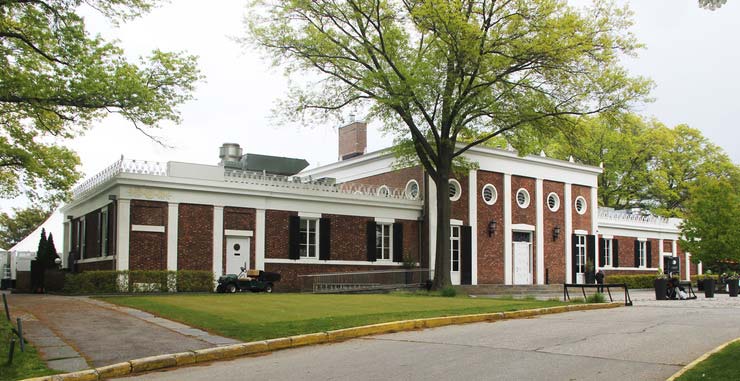

- Orchard Beach Bathhouse and Pavilion

- The Astoria Pool and Play Center (among others)

- The Central Park, Prospect Park, and Staten Island Zoos

- Randall's Island Municipal Stadium (demolished 2002)

- 1939 World's Fair NYC Pavilion (now the Queens Museum)

- Clason Point Gardens low-income low-rise housing project

I am not aware of any published list of Embury's New Deal projects, so I have been working on assembling one myself. At this writing (25 November 2019) I have identified 235 of them. In most cases I can't say to what extent he designed a project personally, or collaborated with other architects on it, or simply supervised; short of digging through mountains of boxes at the Embury archive in Syracuse, we can only rely on official records that name him as architect of a given New Deal project. The current list of these projects is here:

http://kermitproject.org/newdeal/embury/And a gallery of some of his most striking projects here:

http://kermitproject.org/newdeal/embury/gallery/The list is useful in identifying New York City New Deal projects in cases where no other New Deal connection is recorded. By virtue of Embury being on a federal New Deal payroll, any particular project can be classified as a New Deal project if Embury is officially credited as its architect in his Parks Department capacity during 1934-1943.

Eighty years hence, countless people traverse Embury's bridges and highways and tunnels, and visit his beaches and pools and parks and zoos and other creations, without having the faintest notion of how these marvels came to be. In 1965 Embury's son, Edward Coe Embury, paid tribute to his father's New Deal career by designing the marvellous Delacorte Clock[5] for the Central Park Zoo that his Dad had designed in 1934.

In 1995, a New York Times article[6] reported how Embury's descendents were taken by the Parks Department on a bus tour of some of his most famous and enduring New Deal public works. The article concludes: "During the years of the Federal Works Projects Administration construction, while he served as chief architect for Robert Moses, he did as much as anyone to bind the city together and to help it dig its way out of the Depression."

| * | For simplicity, "WPA" is used in this article as a shorthand for any New Deal agency such as FERA, CWA, PWA, or WPA itself, that paid for public works. |

References:

- Mason Williams, City of Ambition: FDR, LaGuardia and the Making of Modern New York, W.W. Norton (2013), p.191.

- Aymar Embury II Papers, Syracuse University, Libraries Special Collections Research Center. Home of Embury's papers and one of dozens of reputable sources for the 600 number.

- "Architect", Talk of the Town, The New Yorker, 7 July 1934, pp.12-13.

- Aymar Embury II, The Aesthetics of Concrete, Pencil Points, May 1938, pp.267-279.

- Delacorte Clock, NYC Parks Department.

- A Family's Ancestor Was a City's Architect, New York Times, 22 July 1995, Section 1, p.23.

- The New Deal in New York City 1933-1943.

- Aymar Embury II, Wikipedia (accessed 4 December 2020). In addition to a brief summary of his NYC New Deal work, the article notes that he served in the US Army Corps of Engineers in World War I and designed the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

- Bill Case, Architect of the Sandhills, PineStraw Magazine, 14 September 2016. Includes some early photos of Embury, and 3/4 of the way down includes about eight paragraphs on Embury's New Deal work.

- Russell J. Whitehead, Some Work of Aymar Embury II in the Sand Hills of North Carolina, The Architectural Record, v.55, no.6, June 1934, pp.505-568.

- Aymar Embury II, biographical sketch at The Cultural Landscape Foundation (accessed 31 March 2022).